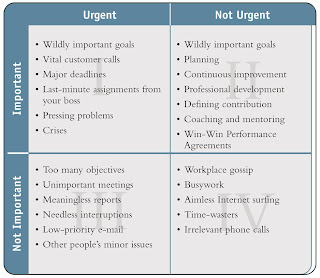

One of Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits (Habit 7, fact fans) is “Sharpen the Saw.” It’s based on the idea of continuous improvement, on the idea that we have to continually learn, continually grow, continually expose ourselves to new interests and influences. Ghandi once said "we open the doors and the windows and allow all the currents to come in” and I think that’s a good philosophy: it’s important to let the tides come in occasionally, to mix things up. It’s not easy to set aside time to do these things – I’ve talked before about the tyranny of the urgent – but if we don’t continually improve ourselves, we’ll get left behind.

So here on the inspired blog, in addition to our regular weekly posts, we’ll occasionally be posting a series of interesting articles and videos for you to take a look at. Hopefully, they will spark thoughts in your mind or provoke a debate. I’d love to know what you think of them, so please do take a moment to leave comments or tick the little box below; the more I know what you like, the more I can deliver it!

This week, we bring you a video by Seth Godin from the ever-reliable TED website; if you’re not paying attention to what both Godin and TED are doing, you really need to give yourself a good talking to. As you watch this video, ask yourself what story you’re telling and how you’re challenging the status quo...